The first person that I baptized on my mission was one of the coolest people I’ve ever met, who we’ll call Tomas here so I don’t have to use his real name or keep on calling him “that one guy.” Tomas told me stories of his youth spent in the White City of Mexico (Puerta Vallarta), dancing on the beach and listening to the up-and-coming band Maná. And, amazingly enough, I even understood some of what he said, despite still barely grasping Spanish.

When my companion and I started on the lesson of tithing, I was a little hesitant to teach it. I hadn’t had much experience in the field at that point (two weeks, tops), but I’d seen enough to know that the people we taught were amount the poorest I’d ever met in the US. Add to that the stories Tomas told us about financial burden he faced in bringing his wife across the border, I was worried about his reaction to a lesson asking for a commitment of 10% of meager his income.

Turns out I had no cause for concern. “I’ve always paid tithing,” he said, “even when I didn’t know which church to join. I figure, the Lord commands me to pay tithing. If the people who take my tithing spend it wrong, it’ll be them who’ll be punished, not me.”

Keep that story in mind while we discuss one of the big criticisms that has been floating around the internet for at least the past couple years: whether The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (I’ll go with LDS Church from now on) should make their financials public.

Since I’m an accountant and a CPA (necessary legal disclaimer: in the state of Colorado only), I’ve felt the need to opine on a few of those Facebook discussions using my personal experience. Despite my best efforts, they always end up way longer than I intend. Below is a (really long) summary of some of the main points.

Financial Statements – A Review

Since I’ve only seen non-accountants request that the LDS Church spill their financial guts (there’s probably accountants who want it too, I just don’t know them), I’m going to assume that many of the people wanting this change have little to no financial background. If you’re already a financial expert, feel free to skip this section, where I briefly review the secular doctrine of financial statements.

|

| “Would God that all the Lord’s people were accountants.” -Moses. Probably. |

Financial Statements are a snapshot into the financial health of a business or organization, designed to allow stakeholders (i.e. a person who has a stake in a business. Not like “Stake Boundary” stake, more like “interest” stake) to determine, on a macro level, the well being of the company.

Different organizations have different requirements for financial statements. For example, if you’re doing a personal budget more complicated than the “check the cash in your pocket” method, you’re going to have some sort of summary of how much money you brought in, how much money went out, and how much money is going to go out (i.e. debts). That’s your rudimentary financial statement.

If you have a small business, your financial statements help you make decisions. If you want a loan from a bank, the bank will almost certainly demand financial statements to help ensure they’ll get their money back. These kinds of financial statements generally span a handful of pages, from a couple pages to maybe twenty. The information contained therein is basically never released to the public, because, frankly, it’s none of the public’s business (literally).

Sliding that size scale all the way to 11, let’s look at large, publicly traded corporations. Their financial statements are required by law, must follow certain prescribed rules (GAAP in the US), and tend to run into the hundreds of pages. Despite rivaling War and Peace in length, the statements are designed to say the very bare minimum, and not a word more, to give investors a snapshot into the company’s past performance.

Keep in mind that financial statements are at a painfully high level. Ask any auditor and they’ll tell you the same thing until they’re blue in the face. It doesn’t tell most of the transactions. It’s not a blueprint on how to run a company. It’s not designed to detect fraud. Although our accounting overlords continually add new rules to try to prevent the next Enron or WorldCom, neither a thorough, expensive audit nor the resulting financial statements are a guarantee to that.

If you’re still awake after that and you want to find out more about the history of accounting, I recommend The Reckoning by Jacob Soll. I know, Accounting History sounds about as energizing as downing an entire bottle of Nyquil, but it’s a pretty good book.

|

| “Every member an accountant.” -David O. McKay. I think. |

Church Financial Statements – What Would It Accomplish?

Okay, so you now know, or can at least pretend to know, what a financial statement is. Here’s where I’m having problems: what would publicly releasing the LDS Church’s financial statements accomplish?

Before you answer that, want to see what you’ll be getting? I found the financial statements for the Episcopal Church, which happened to be put together by my former employer. Go ahead, read through the 2013 report.

So what did you learn? I learned that the Episcopal Church is financially sound right now. And…that’s about it.

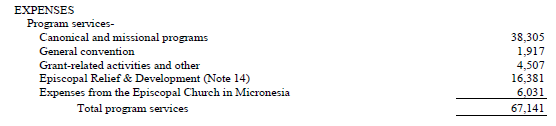

How much do they donate to the poor? How much to give in foreign relief? How much do they use on buildings? I have absolutely no idea. The best we get is this scant breakout here:

What do they consider to be “Canonical and missional programs”? Is “General convention” a euphemism for the priests heading to ComiCon on the church’s dime? And what’s with this “other” amount grouped in with Grants?

In other words, we’re almost exactly where we started. We know how much money they brought in and how much money went out, but they grouped their expenses based on arbitrary categorizations invented by whichever accountant implemented Quickbooks for them.

Unfortunately, their grouping totally fails for me, because those Episcopal financials don’t allow me to voyeuristicly understand how they use their money. Heck, it doesn’t even tell me how much they spent on Communion Crackers!

For them, though, it works. Their goal was likely to prove that they are spending less than they make, and on that point, mission accomplished.

If we were to get public financial statements for the LDS Church, this is about as good as we could expect. Want proof? Turns out the LDS Church has financial statements in the UK (required by UK law). And considering that I haven’t heard a single person mention how great it is that the Church practices financial transparency overseas, I’m guessing the number of people demanding US financial statements that know about the UK financials are in the single digits.

What do we learn from the UK financial statement, anyway? Well, the Church brings in more than it spends, and 97.66% of their expenses are related to “Charitable Activities.” It doesn’t tell us the most basic things us financial voyeurs need to know, like how much is spent on those amazing red and blue cleaning supplies.

I Want Transparency, Not Your Accounting Nonsense

Okay, so you’re not an accountant, and you’re not interested in stuffy financial statements made up by overweight accountants with little green visors and even smaller personalities. You just want more transparency.

But why?

What are you going to do with that information? Do you honestly believe that knowing how much the LDS Church depreciates the Salt Lake City Temple renovations every year will convince you that what goes on inside is sacred? Will seeing how much the LDS Church sends to Africa in financial aide have one bit of bearing on whether Joseph Smith talked with Heavenly Father and Jesus Christ in the Sacred Grove? Does the amount spent on basketballs each year have any relevance on whether or not the Book of Mormon is true?

Look, I really don’t mean to come across as harsh, I just fail to see how financial ledgers, no matter how detailed or how summarized, matter. Either the Church is true, or it’s not. I believe that it is. Yes, it’s absolutely run by imperfect people, and they will make financial mistakes. But like Tomas at the beginning of this post so wisely told me, if they screw up, it’s on them.

|

| I wonder what Circle of Hell Dante would put those who overspent on office supplies (this is the Third Circle, by Stradanus) |

If the LDS Church isn’t true, why would it matter one whit how transparent they are? They are not claiming to be a “good” organization. They’re not trying to be the United Way or March of Dimes. They proclaim to be the only true and living Church on the face of the Earth. If they are not that, there are much more significant problems to address than whether they could have gotten a better deal on the roof of the new ward building. Or even if those tithing dollars are being fraudulently spent.

But Look At the Suffering

The thing is, I get what many people are trying to say. It’s easy to look around the world and see all the suffering, then look at the (non-released) financial situation of the LDS Church and think, “surely we can do better.”

Whether we can or can’t, I really don’t know. As individual members of the Church and followers of Jesus Christ, especially ones living in the wealthiest country in the world (or wherever you are on that list if you’re not in the the US), absolutely. I throw myself into that bucket for sure. All of us can get a little caught up in what should be considered a “want” and what should be considered a “need,” forgetting that the amount we spend on those alleged needs could be better served helping those with real needs.

But can the actual organization, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, better allocate it’s resources to give more to the poor?

The LDS Church recently included “caring for the poor” among their missions, bringing the total missions to four. I don’t think I’m breaking new ground by saying that this new mission takes money. What about the other three? Proclaiming the Gospel, Perfecting the Saints, Redeeming the Dead? All of them take money, too.

Could we ask missionaries to pay a bit more to cover the expenses related to the mission? Maybe, but for many what’s being asked is already a huge burden.

Could we worship in buildings that aren’t quite as nice? Perhaps, but most of the newer buildings are pretty utilitarian, even reusing the same architecture plans to save on costs.

Could we make our temples look a little less nice? On this one, I think not. The new, smaller temples already have several changes to help cut back on expenses, but we can only go so far. This is the Lord’s house, which He has asked us to make them worthy of Him. Going back even to the days of the Tabernacle (Old Testament, not the one on Temple Square), the House of the Lord has always been designed to stand out. Remember, nice stuff for our Lord is good every now and then (see Matthew 26:11).

In other words, 7 billion dollars a year (or whatever the Church actually collects in tithing) is really not that much considering the many expenses we have worldwide.

To put that 7 billion dollars in perspective, I’ve often heard the Church income compared to Gap, Inc. in terms of revenue. Based on my reading of Gap’s 2013 financials, they brought in about $9.6 billion after taking out the cost of clothing (i.e. Cost of Goods Sold). Of that $9.6 billion, they were only left with about $1 billion at the end of the year. That’s over $8 billion a year just to keep a company with about 180k employees running.

No corporation is ever going to be a perfect example, but considering the Church’s millions of members, and its reach across the globe, their operating expenses WILL be in the BILLIONS, even with their relatively small amount of employees.

May I make a quick aside here? My experience as a financial clerk indicate that many wards do not even receive enough in fast offerings to cover their local ward’s needs. These funds really do go directly to those in need. If you’re concerned about the poor of the world, I sincerely encourage you to give a generous fast.

What About The Church’s Other Businesses?

Here comes a bigger sticking point: does the Church really need all these other businesses?

This is a point where reasonable people can disagree. I believe all the businesses, or at least virtually all of them, were started back in the day when the Saints could only rely upon themselves. Many are good organizations and can be used to help others (i.e. Deseret Industries, Orange Farms out in Florida, etc.). Some are designed more as Public Relations item than anything else. The biggest example of that latter point is the $1.5 billion mall in Salt Lake City. Was it necessary? I don’t know. What I do know is that downtown Salt Lake City represents the LDS Church in many people’s mind, and if it’s run down, dingy affair, many will see the Church as run down, dingy affair. It may not be fair and it may not be right, but that is the way it is.

|

| Flickr claims this is the City Creek Center. I haven’t been there, so if it’s not, I blame Ken Lund. |

Back to the point, are these business necessary? My guess would be “no.” It’s not really related to this transparency conversation, but as long as they’re not losing money or distracting from the missions of the LDS Church, it seems unnecessary to jettison them. Besides, selling them off and giving all the money to the poor might be a nice one year boondoggle, but if you run the business so you can continually help people, it seems like it’s all the better.

Like Jesus said, we have the poor always with us, even if we give out a Scrooge McDuck-worthy pile of money (he might not have said that last part).

I had my dad read through this article before posting since he has a lot of experience with finances, and he made another good point that should be added here. Like many charitable groups or scholarship funds, the Church prefers to invest its cash and run operations off generated interest. It’s a good way to run things when you want to be conservative (small c) with your operations and more or less guarantee a set amount of money to keep things going every year.

So how do you invest that money? Well, you could buy real estate, you could invest in stocks and bonds, or you could put the money in the bank. Each one of those has a downside (real estate market could crash, company could be caught up in a scandal or release a caffeinated drink, etc.). The safest, of course, is a bank, but the funds are only insured up to $250,000, and they don’t pay very much in interest (a little over a percent right now).

And what will the bank do with the money? Invest it in real estate and stocks and bonds, taking a large percentage of the interest generated for their time and efforts.

Why not invest the money yourself, which removes the bank’s portion, giving you more to help with your goals? That’s basically what the Church did with the City Creek Mall, with the added bonus of giving them control over the downtown area. Plus helping generate jobs for those hired by the mall isn’t a bad benefit, either.

What Good Would Transparency Do?

Let’s start first with the business side of the LDS Church. Why good would it do to have these financial statements? I can think of only one legitimate reason, and that’s to ensure that they really do keep tithing money separate. But if that’s all we’re after, a credible, independent, third party auditor stating that they’re separate would accomplish the same thing at a fraction of the price. Which I believe is exactly what the LDS Church does right now. Wanting to know the rest of the numbers is like wanting to know the financial standing of a private company like Enterprise Rent-A-Car or Mars Chocolates: it might make an interesting slideshow on Forbes, but it really has no baring on you personally.

Moving on to the religious side of the Church, what good would be accomplished by publicly releasing financial statements? I suppose it could serve as an extra check to make sure the funds are properly treated, but with a multibillion dollar organization, the numbers will be truncated into nearly meaningless oblivion, just like they were in the Episcopal Church example above.

Want to know how easy it would be to hide stolen or misapplied funds in truncated financials? Well, most auditors don’t even consider digging into a number unless it’s “material.” Materiality for a 7 billion dollar company would be AT LEAST $10 million dollars, if not more. So as long as you steal less than $10 million in a not totally obvious way, it won’t even hit the auditing radar.

So, what, then, would transparent financial statements be used for? I suspect the only use would be for people with 1/1000ths of the information as those making financial decisions to loudly proclaim that the LDS Church isn’t making the right decisions. Kind of like Monday Morning Quarterbacking after watching about 3 plays of the game.

|

| I’m not sure who this kid is, what game he’s talking about, or if Lynch is a player or a scheme, but I think he’s right |

And if they weren’t truncated into nearly oblivion, what then? Even if you did watch the game, it doesn’t mean you could have done better. If you really think you can, there’s a way to do that without loudly shouting criticisms over the internet.

Keep in mind that we’re not shareholders. We’re not getting a financial return on our investments. Our donating of tithing is based on our faith in the Lord, not because we expect a 5% dividend.

Heck, we’re not even taxpayers here. We’re not trying to get representation. We’re supposed to give frankly, expecting nothing in return.

What Would It Cost?

I’m on the tax side of the accounting spectrum, so I haven’t actually priced out an audit, nor do I know enough about the LDS Church’s financial structure to come up with an good price even if I had experience. Based on the many audit bills I’ve seen, though I would expect a full audit to publicly release the LDS Church’s financial statements to cost at least $1 million more than whatever services the LDS Church is already paying for right now. That’s $1 million to, at best, scratch a bit of curiosity. There’s no way you’ll convince me that can’t be better spent elsewhere.

Even if the number is not that high, it would not be zero. From a cost/benefit analysis, I fail to see any benefit generated that would support all but the smallest of costs.

So Where Are We?

I don’t believe the LDS Church is hiding some great financial secret: there’s too many accountants at the LDS Church, including some who have turned against the Church, for unethical dealings to not have been leaked by now. Enron had a much shorter life than the LDS Church, and it was dismantled by someone on the inside, not someone reading financial statements. Considering that Enron was stocked full of self interested employees, not people who grew up believing that their organization should be held to a higher standard than everything else, serious Church financial wrong doing would have come out by now.

At best, if we had transparency, you’d get a small group of people complaining that the LDS Church is wrong because it does their finances differently than they would do it, while everyone else would get bored before scrolling to the end of the released PDF.

Going back to the cost, that sounds like a pretty low benefit to justify virtually any expense.

If the LDS Church does one day release their finances, so be it. In the meantime, there are much better causes to dedicate our time to. May I suggest helping the poor instead of complaining that the Church isn’t helping them enough?

In the end, money isn’t what my testimony is based on, and yours shouldn’t be, either. We should be more like Tomas, having the faith to know that the Lord will bless us for following His commandments…even if others don’t.

——

But wait, there may be more! If you liked all this tax and accounting stuff, check out my Tax Blog at CreativelyAccounting.com. Or follow me on Twitter @TimJGordon